In an industry dominated by polished demo videos and tightly controlled product narratives, UC Berkeley’s latest humanoid projects Berkeley Humanoid and Berkeley Humanoid Lite land with a very different energy. There are no theatrics, no dramatic set pieces, no attempt to mimic the presentation style of robotics companies positioning themselves as the “future of labor.” Instead, these machines appear in the kind of environments where real robots are expected to work: uneven ground, loose dirt, random slopes, the type of terrain that doesn’t get swept before filming.

And yet, these are the robots making many researchers pause.

Not because they look futuristic they don’t.

Not because they perform backflips they don’t.

But because they challenge a fundamental assumption the field has held for more than a decade: that advancing humanoid robotics requires massive budgets, enormous teams, and hardware expensive enough that failure is something to avoid at all costs.

Berkeley’s researchers built a system where failure is the starting point.

The Case Against Polished Robotics

Most humanoid research labs operate under constraints that force conservatism. When your machine costs hundreds of thousands or in some cases, millions of dollars, everything you do is calibrated to minimize risk. Experiments are controlled. Surfaces are even. Movements are predictable. Anything unpredictable is redesigned out of the workflow.

This produces impressive videos, but not necessarily robust robotics.

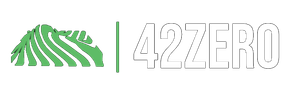

Berkeley’s team approached the problem from the opposite direction. They built a lightweight, mid-scale humanoid specifically to tolerate the kind of failures that normally halt experimentation. The robot is cheap enough to withstand real trial-and-error. It’s simple enough that repairs don’t require specialized manufacturing support. And it’s sturdy enough to remain functional through the repeated impacts that come with reinforcement-learning training cycles.

The researchers describe it not as an engineering showpiece, but as a tool something closer to a lab notebook than a corporate demo asset. The priority isn’t to impress; it’s to iterate.

A Practical Approach to Locomotion Research

The most notable thing about Berkeley Humanoid is not its appearance or even its price point. It’s the environments where it’s tested.

The robot is deployed on:

- Rough outdoor paths

- Downhill dirt slopes

- Irregular terrain that shifts under its feet

- Spaces that normally cause researchers to hesitate

During these tests, the robot displays what many teams consider a benchmark capability: a narrow sim-to-real gap. That is, controllers trained in simulation transfer to the real robot with minimal catastrophic failure.

This matters. For years, robotics researchers have tried to reliably transfer learned behaviors from virtual environments to physical machines. Each group has made progress, but results are often brittle requiring extensive domain randomization, complicated safety layers, or expensive hardware built to survive failure.

Berkeley’s controller is comparatively simple. It doesn’t rely on exotic modeling or complex probabilistic frameworks. Instead, it applies reinforcement learning techniques that have become increasingly standardized, combined with hardware that isn’t financially or physically fragile.

The result is a robot that performs human-like walking, directional changes, stability recovery, and even single- and double-leg hopping a task that typically demands heavier, more costly machines.

This is a significant engineering statement: mid-scale humanoids do not require high-end materials or corporate-grade budgets to achieve dynamic locomotion.

The Lite Version and the Open-Source Shift

If Berkeley Humanoid is a research tool, then Berkeley Humanoid Lite is an open invitation.

Released under a permissive Python License, the Lite platform includes:

- A complete hardware stack using 3D-printed gearboxes

- Real robot low-level control code

- Reinforcement learning training pipelines

- Full simulation environments for Isaac Lab

- Teleoperation tools

- Motion capture tools

- All URDF, MJCF, USD models

- A documented directory structure for reproducibility

This is the kind of material that is usually locked behind NDAs or shared only within private research consortia.

The Lite platform is different. It is structured like a mature open-source repository, not a quick academic release. The directories follow conventions recognizable to anyone working with Isaac Lab or physics-based robotics. The scripts folder functions as a control center for training, evaluation, and deployment. The documentation makes it possible for small teams student organizations, hobbyists, underfunded labs to understand how the system works rather than simply replicate it.

The intention is straightforward: enable more people to run serious humanoid locomotion research without requiring access to elite facilities.

Why This Matters for the Robotics Field

For years, humanoid development has been concentrated in the hands of a few organizations with substantial capital:

corporations like Figure, Sanctuary, Toyota Research Institute, and multinational labs with the resources to build and maintain costly platforms.

Berkeley’s work doesn’t aim to compete with these companies. It aims to widen the base of contributors.

There are three major implications:

1. Lower Cost Means More Experimentation

When a robot survives failure and doesn’t bankrupt its owner when it breaks researchers run riskier, more frequent tests. This accelerates learning in ways no simulation stack can compensate for.

2. Open Hardware Creates Network Effects

Once low-cost humanoids become reproducible, independent labs can begin sharing modifications, improvements, and controller variants. Innovation shifts from centralized R&D to distributed problem-solving.

3. Skills Development Becomes Accessible

Students who could never access high-end robotics hardware now have a platform built for education and experimentation. This reshapes pipelines for future researchers.

This model resembles what happened in computing when early open-hardware and open-software ecosystems proliferated. Innovation didn’t come from a single organization it came from thousands of small contributions.

A Different Kind of Robotics Story

The robotics world often treats humanoids as prestige projects, indicators of institutional strength. The Berkeley humanoids, by contrast, are intentionally modest visually minimal, materially practical, and designed around repeatable learning rather than presentation.

This doesn’t make them less impactful. It arguably makes them more so.

The significance of the project is not about what it can do today, but about who can build on it tomorrow. The Lite version’s $5,000 bill of materials places it within reach of independent creators, high-school robotics programs, community labs, and early-stage researchers operating far outside major institutions.

This shifts the narrative from exclusivity to participation.

The Independent Researcher Scenario

Consider a student working alone with access to a 3D printer, standard servos, and mid-level coding skills. Before Berkeley Humanoid Lite, their options for experimenting with biped locomotion were limited to tabletop-scale hobby robots, virtual simulations, or heavily simplified prototypes.

Now, they could assemble a mid-scale humanoid capable of meaningful locomotion experiments using a documented, actively maintained open source stack.

This creates a realistic pathway for contributions from unexpected places something robotics has historically struggled to enable.

What Comes Next

Whether Berkeley Humanoid Lite will spark a larger movement remains to be seen, but the indicators are there:

active community channels, early forks, interest from smaller labs, and widespread discussion among researchers who see value in democratizing humanoid experimentation.

What’s clear is that the project introduces a credible alternative to the industry’s dominant approach. Instead of waiting for corporations to set the pace, it encourages a broad range of contributors to explore solutions locomotion, reinforcement learning, mechanical design that scale in ways centralized development never could.

In other words, Berkeley’s humanoids do not compete with multi-million-dollar robots. They challenge the assumption that such robots are the only way forward.

A Final Observation

Humanoid robotics has long been treated as a discipline requiring perfection before participation. Berkeley’s approach reframes the field: participation first, perfection later. Build something people can break, fix, and improve and the ecosystem takes shape on its own.

If that ecosystem grows, the next major step in humanoid research might not come from a corporate keynote or a government-funded lab. It might come from a student in a small workshop, running a training script on commodity hardware, watching a low-cost robot test its limits on uneven terrain.

The story of Berkeley Humanoid is not about spectacle.

It’s about access.

And access when paired with open tools has a history of changing fields far more than any polished demo ever will.